We’re poking our heads out after what’s felt like a nuclear winter for early stage consumer startup investing in the United States. The billowing smog from big tech has, with a few exceptions, blocked out the sun. New opportunities promised by venture prophets proved false. Apple’s watch didn’t turn into a haven for super popular apps and the company’s augmented reality headset hasn’t materialized. Hardly anyone owns virtual reality gear. The price of bitcoin reached an all-time high this week, but where are all the great companies built on the blockchain? And audio, well, it may be a false god.

Venture capitalist M.G. Siegler wouldn’t quite humor Chernobyl-level devastation. “At a high-level, I think that's roughly correct. I don't think it was as dire as a nuclear fallout might make it seem like. It's definitely been slower relative to what we've seen in the enterprise side,” says GV’s Siegler. “Everyone was looking for the next quote-unquote platform. We had the iPhone in 2007, and it's been 13 years.”

Venture capitalist-turned-Facebooker Eric Feng analyzed Y Combinator startups just before the pandemic hit and showed that they’d drifted to majority enterprise. About one-third of Y Combinator startups in 2019 were consumer startups, down from as high as 80% during one batch in 2006. Feng found that in 2019, for the first time in recent memory, the majority of seed deals across the industry had been in enterprise companies.

In the last decade, consumer companies like Meerkat exploded and then they exploded. Meerkat took off at SXSW in 2015, only to pivot a year later. (The company turned into Houseparty, which sold to Epic Games for an undisclosed sum.) Sequoia’s investments in YikYak and Whisper are two notable consumer disappointments.

“There have been a lot of false starts in purely social,” says Jeremy Liew, an early investor in Snapchat.

Saying that a space is over, or back again, is always a little fuzzy. For one, the lines between enterprise and consumer investing have gotten muddy. Slack is an enterprise business (its customers are businesses), but it has a viral consumer adoption strategy. Dollar Shave Club is a consumer business (its customers are regular people), but it sells a recurring subscription service like many enterprise SaaS businesses. Two, there are always plenty of exceptions. Robinhood is a dominant consumer financial company. Gamer chat company Discord is raising money at a $7 billion valuation. Nextdoor, another Benchmark Series A, is going strong and could be a 2021 IPO candidate. And we’re about to see Airbnb, DoorDash, Affirm, and Roblox go public. Three, the term consumer can mean different things in different breaths. One second it is a broad category that includes direct-to-consumer ecommerce businesses like Warby Parker and the next it just means the next Instagram.

But if you talk to investors it’s obvious there’s been a mood shift.

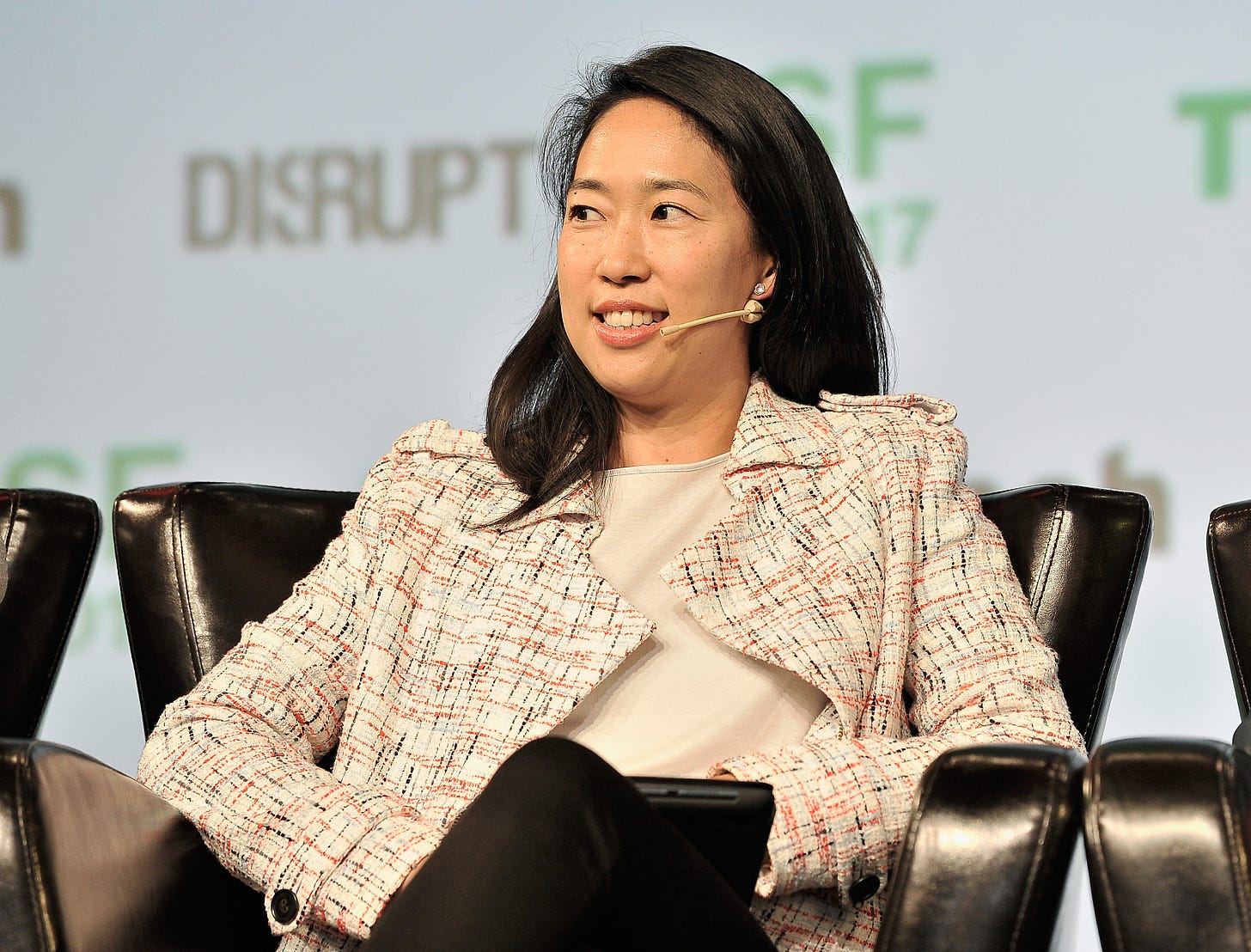

Investor Li Jin says people would ask her why she insisted on investing in consumer companies instead of software as a service businesses. “That was the first period of my investing career: People constantly being like, Are you sure you want to do consumer investing? What opportunities are even left?’” she recalls. “No one asks me that any more.”

Early stage consumer is officially back.

And there’s a maledictive proximate cause — the pandemic.

“It's created changes in consumer behavior like we've never seen before,” says Floodgate partner Ann Miura-Ko.

Danielle Li — the chief executive officer of the QVC for your phone company, PopShop Live — walked into Floodgate’s Menlo Park office on March 5. It would turn out to be Miura-Ko’s last in-person pitch before the lockdown. “The next week I moved everything to Zoom.” The duo had a call to discuss terms on March 12 and then Miura-Ko led a $3 million seed round with Abstract Ventures. Miura-Ko — a thesis-driven investor in an industry where too many follow the herd — had been looking for a digital online shopping network for years and she’d finally found it.

Then, the pandemic hit the United States. Floodgate warned portfolio companies that it could be devastating. Instead, the lockdown meant that people were bored with nothing better to do than to play with their phones. “By summer, you could tell that we were totally wrong,” Miura-Ko says. The pandemic has been a boon for startups jockeying for people’s attention, for telemedicine companies, for online banking services, for delivery companies, for education-technology startups, and for any company that makes it easier to stay at home.

The pandemic seemed to accelerate PopShop’s engagement. A few months later, Benchmark, Andreessen Horowitz and Lightspeed Venture Partners jockeyed for a spot in the round, as The Information reported in November. Benchmark’s Matt Cohler is joining a new board for the first time in several years. Lightspeed participated.

The deal came on the heels of Andreessen Horowitz’s Andrew Chen beating out Benchmark’s Sarah Tavel to lead an investment in audio chat room app ClubHouse at a roughly $100 million valuation in May. (The two firms have a history of fighting over deals. I’d heard Benchmark looked at Wonderschool and that Bill Gurley started talks with Incredible Health but then negotiations fell apart. Andreessen Horowitz’s Jeff Jordan ended up investing in both companies.)

By my estimation, if you want to bet on a firm to win a hot Series A consumer deal, you’d pick Andreessen Horowitz, with Benchmark close behind. If you had to pick a venture capital firm based on who you’d trust to actually return the fund with that investment, you’d pick Benchmark.

Nipping at their heels, you’ve got Lightspeed and Bessemer — two dominant enterprise firms with some strong consumer investors. Sequoia is always relevant. I’d put Spark (really Nabeel Hyatt) and General Catalyst in the conversation. Nikhil Basu Trivedi should be a potent contender when his new firm is in order. (He recently published a post arguing the consumer investing never died.) Kirsten Green at Forerunner has been particularly strong in ecommerce. Garry Tan at Initialized has built quite the brand and stays close to the YC companies, even though his more famous partner Alexis Ohanian left to start his own firm. Matt Mazzeo at Coatue is big in the early stage. I’ve already introduced Siegler, and Miura-Ko invests before many of these investors.

Andreessen Horowitz recently announced that it has nearly $16.5 billion under management. “That's the thing with Andreessen, they can do everything because they have this enormous fund,” one VC mused.

So while a16z is fighting with a club, Benchmark has to bring a scalpel. My interest was piqued when Tavel said on Harry Stebbing’s The 20 Minute VC that she’s “on six boards.” She’s only announced two of them. Tavel is among the most important consumer venture capitalists of the moment, so I’ve been eager to figure out what exactly she’s investing in.

She wouldn’t tell me. “I don't announce my deals,” she told me in a phone interview. “I have a thesis on consumer that so much of what's happening in this startup world that we all live in is the me toos, look at what happened with Clubhouse. It became this huge thing and all of a sudden there are 50,000 Clubhouse clones or Clubhouse competitors.” Tavel said she thought the best consumer startups were “underestimated from the outside.” “Why aren't there 15 Robinhoods? No one thought it would be a good business until it was a great business. There are so many — Etsy, I think about Etsy all the time. There are so many of these companies that people underestimate them from the outside, so it didn't invite competition. So it gets to a point where you've won, you have the economies of scale, the network effects whatever it may be.” She concluded, “I want my companies to be underestimated.”

She’s not the only prominent investor who has been trying to keep their deals quiet. Her old mentor at Bessemer, Jeremy Levine, has a similar philosophy. He says announcing deals is “just not wise — the ideal first time someone realizes how successful you are is when they read your S-1.”

Sorry, but I don’t like secrets.

I hear that Jeremy Levine led the Series A investment in English-language tutoring company Cambly and that Tavel led the subsequent round. The company was founded in 2012 or 2013 (depending on which founder’s Linkedin bio you trust) by two former Google software engineers. The company has job postings for marketing jobs in China, India, South Korea, and Russia.

I also hear that Tavel invested in the TikTok-for-beauty company Supergreat. That makes sense given Tavel’s experience as an early investor and then product manager at Pinterest. The company has rave reviews on Apple’s app store. Supergreat encourages regular people to record themselves applying and reviewing makeup.

Tavel has publicly announced Chainalysis and Hipcamp. (The word is that the camping company has had talks to raise at a roughly $500 million valuation from Mary Meeker’s Bond Capital and Danny Rimer at Index. There was talk that Benchmark-friend Meg Whitman might join the board. I’m not sure where all that stands.) That gets us to four. I couldn’t figure out her other two investments. Who knows how many undisclosed investments Levine has. So it goes without saying that there are exciting consumer deals getting done that we don’t even know about.

Between her time at Bessemer and Benchmark, Tavel took a brief detour at Greylock. I don’t get what’s going on over there. I was reminded of the firm when Josh Elman announced that he was going to go work at Apple Monday. Elman had been the definition of hype-riding consumer investor in the 2010s. He bet on Meerkat (and helped the company pivot to Houseparty). He made disastrous investments in a smartlock company Otto and Robin Chan’s Operator. So at the time, I would have told you that Elman was the embodiment of blindly enthusiastic consumer investing. His standing at the firm cooled. Elman departed Greylock for Robinhood in 2018. Now some of his investments from his years at Greylock are looking much better in hindsight, namely Discord. Elman backed Musical.ly, which was acquired by ByteDance. I’ve also heard that Elman was at one point very close to investing in Snapchat at Greylock, but it fell apart after it became public that the firm invested in rival, MessageMe. And even though Elman didn’t last long at Robinhood, his decision to take the job was prescient. Of course, a lot of investors look great in a roaring bull market that’s been tipped toward tech in the pandemic.

Greylock’s David Sze is still a prolific consumer investor with Roblox and Nextdoor. David Thacker joined Greylock from Google this summer.

A couple quick notable companies: Lunchclub, a LinkedIn for video-type company, raised at a valuation of over $100 million in a round led by Coatue and Lightspeed Ventures. The company went from in person meetings to digital ones in the pandemic. Niko Bonatsos, at General Catalyst, led a $20 million Series A in Bunch, a video chat app for gamers. I get the sense that Suhail Doshi’s browser-enhancement company Mighty is buzzy. Lightspeed Venture Partners announced a $45 million Series B in home schooling platform Outschool in September. In October, GV announced a seed round in the company that makes an audio app called Locker Room. Lightspeed also participated in that round. Phil Libin’s Mmhmm exists in that ethereal plane between consumer and enterprise. Sequoia’s Roelof Botha invested in the company’s seed and Series A.

While the pandemic seems to be driving tech adoption, I also think that there’s a sense that investors just decided to like consumer investing again. They gave up on waiting for a platform, concluded that people were sick of Facebook, and started cutting checks. They learned to stop worrying and love consumer apps.

“This is obviously purely anecdotal and finger in the wind, but it does feel like people are more open and receptive than they have been to try new apps and services,” Siegler said. All the big companies' products seem to be converging, each with its own stories feature. “People are willing to try totally new things because these old things are starting to feel the same.”