I’ve been dragging my feet on writing about Andreessen Horowitz’s much-anticipated new publication, which the firm revealed Tuesday. On the one hand, I played some part in helping to spark the media uproar over Andreessen Horowitz’s “go direct” strategy with The Unauthorized Story of Andreessen Horowitz — a profile of the firm’s communications guru, Margit Wennmachers. On the other hand, I quickly came to see the backlash to Andreessen Horowitz’s ambitions as overblown.

But people have been asking me what I think since Andreessen Horowitz launched their new publication, Future, and since Anna Wiener penned her version of the Andreessen story for the New Yorker1. And I do have some opinions as to how this whole discussion has gotten muddled.

First, here’s my view on Future2. It’s a bunch of essays. They’re not competing with reporters. Maybe they’re somewhat similar to an op-ed page or Wired. As Wiener points out in her piece, the conflict of interest disclosures on some of the pieces could be better. I really don’t have much of a problem with the publication overall. I’ll be interested to see if the firm can keep the content flowing. It looks like they published a ton of content when they launched on Tuesday and their production schedule has been slow since then. The firm wasn’t breaking news or writing the sort of scene-heavy feature you might read in a newspaper or in a magazine. If you restricted your media diet to only the stuff published in Future, you’d be pretty oblivious to most of what’s going on in tech.

Matt Yglesias points out that Future fails to do propaganda well. There’s a certain cunning subtlety that it lacks.

If I have a critique of Future, it’s that in a very non-VC way, they are not thinking big enough.

The purpose of the publication is to foster a tech-positive media niche. But if you read it, that purpose is much too obvious. If you disagree with the tech-positivity worldview, you’ll find it immediately off-putting. If you sympathize with the tech-positive worldview (as I do), you’ll find yourself constantly on guard for things to make fun of to prove you’re not a dupe. A lot of the content that is not cheerleading for tech positivity is like weird industry insider stuff. This is not the way.

What they ought to be doing is thinking like Rupert Murdoch, especially in his newspaper guise.

…

The way forward is not to build a publication around tech positivity — it’s to build a publication that’s good and that weaves tech positivity themes into its coverage.

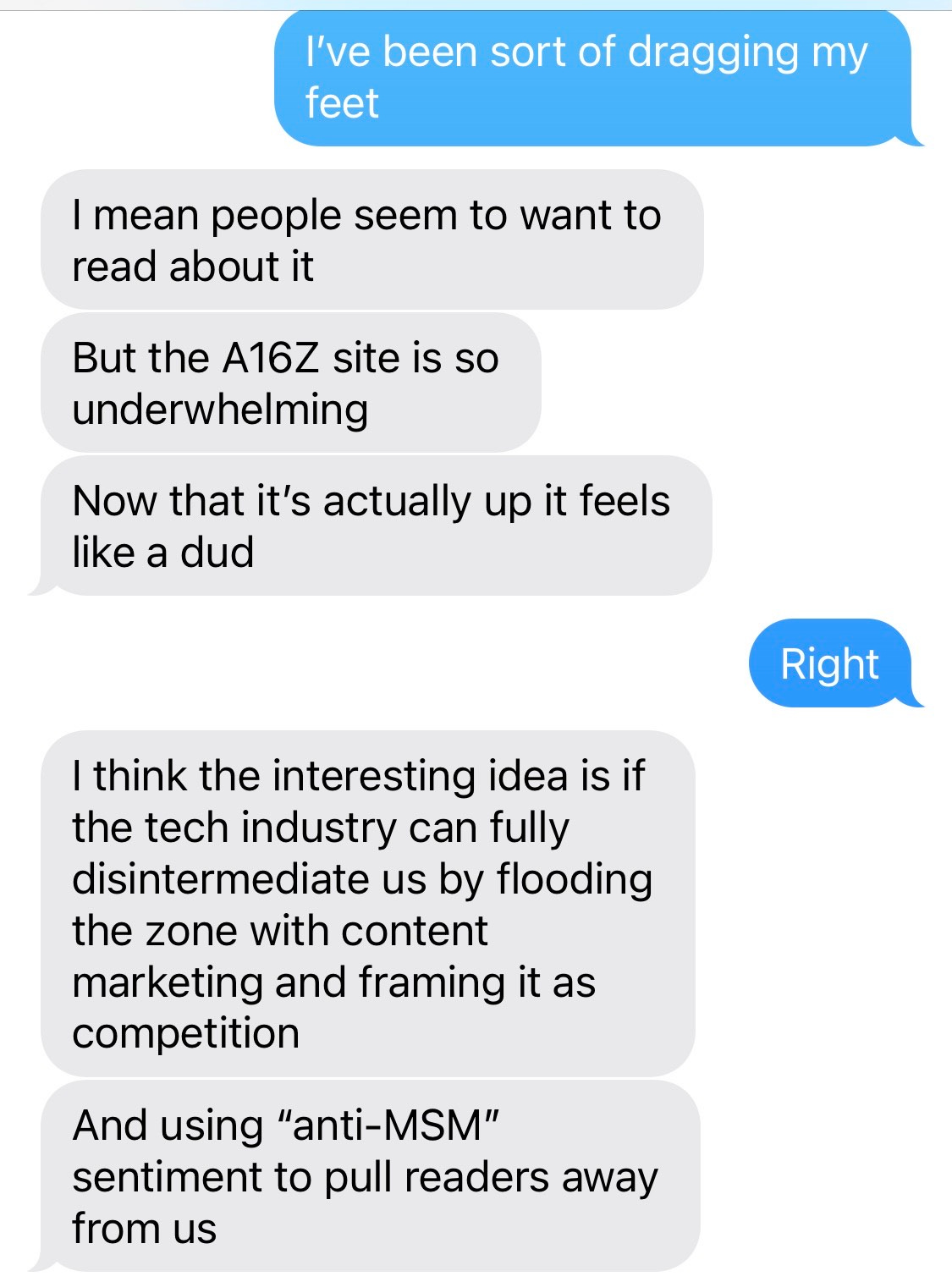

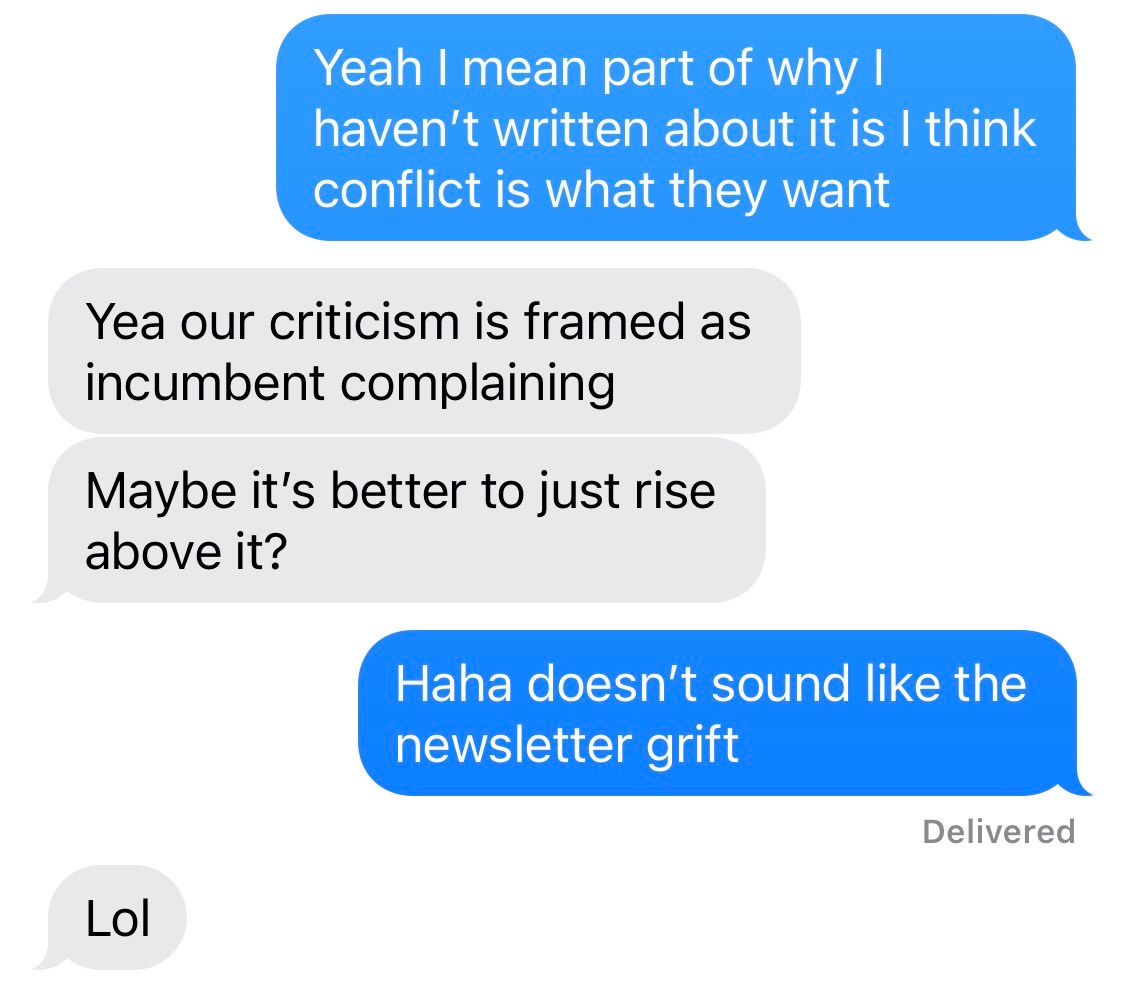

Here’s a text exchange3 with a reporter at one of the big news outlets that finally convinced me to weigh back in on this whole saga and sums up my off-the-cuff take on all of this nicely.

Why Non-Cooperation Is Bad Even If You Detest the Media

I think there are two sets of issues here. Slow Ventures partner Sam Lessin4 has been making a compelling case for why avoiding the media only pushes the press to write more negative stories — and not out of some sense of retribution. I thought this was an interesting back-and-forth with angel investor Bobby Goodlatte.

I have another concern: non-cooperation makes it harder for the media to get the facts right and to follow the reporting. While in-depth stories inherently have some sort of angle, when they’re done well, the narrative is determined by the facts journalists gather by talking to sources5. Good journalism reveals facts that might be used to contradict the thesis of a story.6 While my piece on Andreessen Horowitz had an explicit point of view, it was well-read because it offered new facts that people with all sorts of perspectives wanted to know. That Wennmachers talked to me off the record helped to inform that narrative.

I’m going to confess a bedrock belief of mine:

We live in a fog.

Set aside uncertainties about how the material world works, though there are many. Forget your epistemic self-doubt. Push away questions you might have about the spiritual realm or the soul. There are a lot of big questions that we pretend to know the answers to day-to-day just to get by. Personally, I’m able to hold off these existential crises.

But I’m professionally plagued by what you might call social truths. Who holds power in a society? How are decisions made? Who is culpable for what happens? What are people’s motivations? Who is really getting rich? What are they doing with all that money?

To understand the material world, you might study physics. To resolve those epistemic questions, you could turn to philosophers. For questions of the soul, you might ask a minister. But for these social questions in the short-term you’re basically stuck with journalists.7 Definitely, we get a lot wrong. We’re limited by the fads and fixations of present day — but we’re really your best option. For all the hate Maggie Haberman receives on Twitter, she was the one telling you what was happening in the White House. That’s not the natural state of the world. When a poorly sourced reporter covers a beat or when sources wane8, you will suddenly learn less about what’s happening in one area or another. The attention economy will surface other content to distract you from what you don’t know — but there are really a lot of facts about the world that won’t come to the surface without diligent reporting.

We’re left trying to build a mental model for how the world works in this fog. In tech, we know very little about what leaders like Peter Thiel or Marc Andreessen are up to on a day-to-day basis. We get only snippets of their actual ideologies. Thiel famously hid the fact that he was funding the lawsuit to bring down Gawker! We learned about it because Ryan Mac and Matt Drange reported it.9

So spend all the time you want announcing your new product launch on your company’s corporate blog. But if you’re celebrating cutting out the media, then you’re giving powerful people aircover to thumb their nose at impertinent questions that you too would probably like the answer to. I laugh when many of the same people who trash the media on Twitter regularly tweet out links to news articles. Your view of the world is shaped by what you read in the media whether you like it or not. Future isn’t going to replace the media, but it does make it easier for Andreessen to get his message out without facing questions from prying reporters.

And the technology industry isn’t just culpable here because there’s a simmering cultural aversion to the media and to the criticism that it brings with it. The very technology tools Silicon Valley built pushed media toward the clickbait they detest.

Maybe subscription newsletters like this one will help rebuild some of the reporting that’s been lost. For my part, I’m trying to find a balance between reporting10 and opining.

While Andreessen’s new publication might have a more optimistic point of view, Future is pumping out a form of content that the internet is already chock-full of these days — takes.

Wiener quoted my original article in her piece. I thought the short quote made me sound worried about Andreessen’s media operation when I was mostly concerned about their non-cooperation with the media and how the media operation enabled that. The positioning of the quote in the story also gave the impression that I was reacting to the announcement instead of helping to break the news.

What an amazing URL. Andreessen Horowitz bought Future.com but is redirecting to future.a16z.com.

Don’t worry friends and confidants, this person said I could publish the exchange anonymously.

Sam Lessin’s wife Jessica Lessin owns and runs The Information, so Sam has a close view of the media business. You can read Sam’s full argument here.

I feel like some of the backlash to reported stories in tech came in response to a slew of stories sourced to disgruntled current and former employees. The Verge’s story about Away was a controversial example in this genre.

I do think we go through phases where reporters are all searching for similar types of stories. But I can tell you, I reported out a disgruntled workplace story but never published it because the workplace problems didn’t seem damning enough.

But I think the fact that some angry current and former employees can mar a company’s reputation is actually an argument for cooperation with the press. When reporters are only allowed to talk to the type of employees who are willing to ignore their NDAs, then even a fair-minded reporter is going to come to a pretty negative conclusion from what they learn. This is why I think even employees who like their bosses should talk to reporters off the record. You don’t have to say anything bad but you can give a clear-eyed sense of how the average employee feels.

Covering business, it’s a lot harder to get a full picture of what’s going on than say covering politics. Companies aren’t subject to open records requests and there aren’t competing political parties to dish on each other. And companies don’t always feel the same obligation to the public to explain what’s going on. That means that business reporters, in particular, are biased toward the people who are willing to speak openly and honestly.

Here’s a totally random story about chaotic late-night partying in Washington Square Park that I enjoyed. It’s a great example of presenting both sides of a story and letting the reader decide what they think about it.

Or sociologists, economists, and eventually historians. Certainly academics are better at poring through the data or pulling together broad trends, but if you want accounts of what’s happening in the corridors of power, you’re stuck with journalists.

Once Reince Priebus was cut off from the information flow, the colorful depictions from inside the White House seemed to cool off a little. My speculation — but Anthony Scaramucci seems to agree with me!

Some reporters will scoff that the best information isn’t going to come from powerful people directly anyway. And I agree with that to an extent. But I think the negative sentiment toward the media among powerful people in tech should worry reporters because anti-media sentiment in tech erodes the moral prerogative that people otherwise feel to leak information to the press.

Scoop: I hear Andreessen Horowitz is in talks to lead an investment in Sourcegraph that values the code search company at about $2.6 billion. I hear the company’s annual revenue run rate is just over $10 million. Sourcegraph CEO Quinn Slack and Andreessen Horowitz’s press team did not immediately return emails asking for comment.

Fascinating how media is the news vs. reporting the news right now. Creator economy, editorial vs. independent journalism, social audio, algorithm news feeds, subscriptions vs. ads, a16z et al. Appreciate all of your insights on it here, thx Eric.