Good Times in The Great Revaluation

Exclusive slides from Laurence Tosi + a16z's view on the downturn

You know the market has taken a tumble when venture capitalists feel the need to remind the less numerate among us how percentages work. You need to grow by 100% to make up for a 50% loss.

Andreessen Horowitz’s growth investor David George did just that on the latest episode of The Good Time Show. “The crazy thing is — I mean, this is simple math so bear with me: When you’re down 80%, even if you go up another 50% — you’re still 70% off your overall high.”

With the NASDAQ Composite down 16% over the past month and down 28% over the past six months, venture capitalists have started giving their portfolio companies tips on how to navigate the stock market downturn.

It’s an important moment for thought leadership.

Thankfully, investors aren’t just dishing out basic arithmetic.

On March 9, Logan Bartlett at Redpoint Ventures posted his own “State of the Current Market.”

On May 13, David Sacks’ venture capital firm, Craft Ventures, published the advice that it’s giving to founders.

George’s appearance on The Good Time Show Monday, along with Andreessen Horowitz partners Marc Andreessen, Steven Sinofsky, and show co-host Sriram Krishnan, served as an informal public update on the firm’s thinking about the market downturn. (On May 13, George and a colleague also posted “A Framework for Navigating Down Markets.”)

Also on Monday, Lightspeed Venture Partners tried to put a happy face to the worried markets with “The upside of a downturn.”

For this piece, I also reached out to Laurence Tosi — who runs the investment firm WestCap Group to get his take on what the markets mean for startups. As the former CFO at Blackstone and Airbnb, Tosi is an authority. Tosi agreed to send me some of the internal WestCap research that he’d shared privately with his portfolio companies’ founders. He’s calling this reset the “Great Revaluation.”

a16z’s View on the Downturn

The New Yorker once called Marc Andreessen “Tomorrow’s Advance Man.” If the magazine had felt less charitable, it might have labeled him “Tomorrow’s Hype Man.”

Andreessen and the venture capital firm he co-founded have been driving up startup valuations ever since Andreessen Horowitz was founded in 2009. Sure, Tiger Global and SoftBank have since pushed profligacy to new limits. But Andreessen Horowitz will always be the OG when it comes to doling out speculative startup valuations.

So you can imagine that I was on the edge of my seat listening to Andreessen talk about the dour financial markets.

Recording the Good Time Show, Andreessen had what looked to be an $842-a bottle single malt whiskey on hand. He offered a sober perspective.

“There’s two kinds of private tech rounds happening right now — at least that I can see,” Andreessen said.

“There’s the ones happening at the old prices,” Andreessen said. “Or they’re rounds that were already almost done by the time things changed.”

“What I haven’t seen yet is rounds happening at the new prices, which is the next card that will turn over,” Andreessen said.

Andreessen Horowitz continues to invest. “Speaking for our firm,” Andreessen said, “We continue to be in market. We continue to be in business. We will continue to do rounds. We’ll continue to make investments — but if this downturn in price and economic activity continues, then your prices will definitely reset.”

That’s one point that I want to highlight here: Many of the firms that are sounding the alarm about falling prices are still out investing. Craft Ventures predicted that a recession could last 1.5 to 2 years, but the firm is also continuing to make growth investments.

In fact, there’s an argument that venture capital firms are filling the void left by larger investors like Tiger Global, SoftBank, and Altimeter as those firms slow or halt their growth stage investments.

Recent notable venture deals

Rippling raised $250 million in a round led by Bedrock Capital and Kleiner Perkins at a $11.25 billion valuation.

Deel raised $50 million at a $12 billion valuation with existing investors —Andreessen Horowitz, Spark Capital, and Y Combinator — taking a big part of the round.

Supabase raised $80 million from Felis, along with Coatue and Lightspeed.

Tailscale raised $100 million from CRV and Insight Partners.

So investors are sounding alarm bells while making opportunistic investments at the same time.

On the Good Time Show, the Andreessen partners were joined by solo capitalist Elad Gil.

Gil said, “We actually haven’t seen any real carnage yet. We haven’t seen the layoffs at scale — you know, the things that tend to happen when money really dries up. And so I think a lot of people are either uncertain or they’re in denial.”

“I think where it gets really tricky or dangerous right now is the B or C round,” Gil said. “Because a lot of people raised $1 billion round with $10 million in revenue. And if you look at public comparables, you need something like $100 to $150 million in revenue to support a $1 billion market cap — at least for today’s public companies growing at 20-40%. And so that really means that the bar has gone up dramatically in terms of what a unicorn valuation means. So, it’s quite likely that a third of the unicorns or half the unicorns are going to really have to be focused on cash management to grow into that valuation over the next two to three years.”

Sudden Honesty About Excesses

If you’re going to understand the period that we’ve entered, you need to familiarize yourself with the I Think You Should Leave meme, “We’re All Trying to Find the Guy Who Did This.” I already referenced it in an earlier post about the downturn — but the meme flashed into my mind several times while listening to the Good Time Show conversation.

“I think one of the distortive effects of that last environment was that every round founders would take out secondary — they would sell stock themselves,” Gil said.

That was quietly a big theme in 2021 that no one wanted to talk about: Founders cashed out long before their companies had proved sustainable value. It was contrary to everything Silicon Valley is supposed to believe in — but making founders rich helped firms get into deals they might not have won otherwise.

It’s a trend that was almost certainly enabled by Andreessen Horowitz. Now the firm seems to be trying to get ahead of what will be one of the main criticisms of the last ten year’s excesses: Who got unduly rich off the wild speculation?

In classic venture capital fashion, Andreessen maligned wasteful trends in the startup industry that his firm’s big checks helped to foster.

Andreessen observed that many startups haven’t been truly chastened by the downturn so far.

Founders are saying they won’t increase their burn rate, Andreessen noted.

“It’s like, you know, tiny little applause,” he said.

He mocked companies for keeping their kombucha bars and their masseuses.

He envisioned those companies’ founders saying, “We’re going to keep the gourmet vegan chef — we’re going to keep everything we have. We’re just not going to increase any of it.”

Andreessen said, “The level of inventiveness in the last 10 years that companies have found to spend money is just staggering.”

Laurence Tosi’s Market Analysis

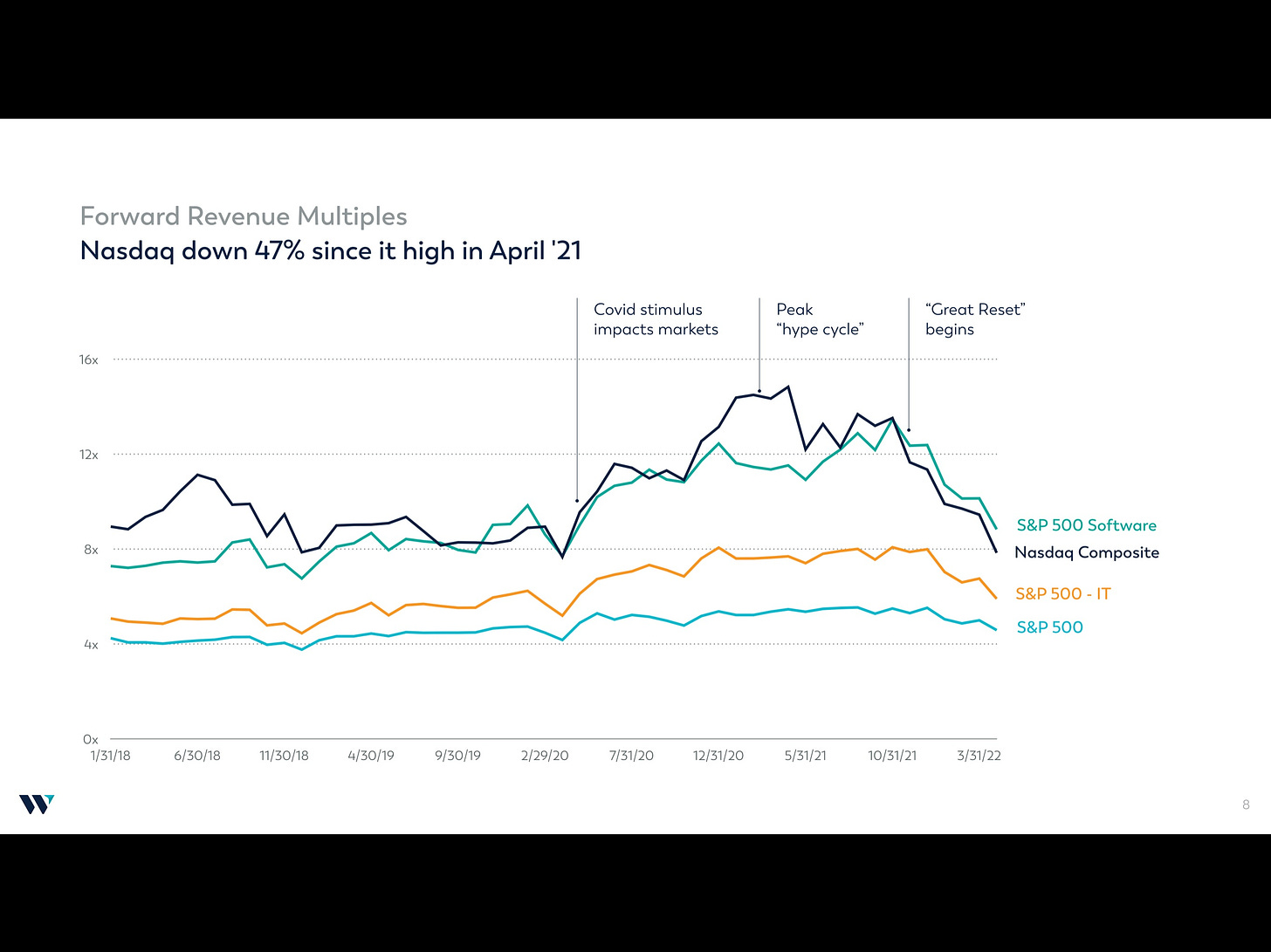

Low interest rates during the pandemic helped send tech valuations soaring in 2020 and 2021. Then the Federal Reserve, facing rising inflation, moved to raise interest rates.

Valuations started falling.

Crossover investors like Tiger Global and Altimeter got caught in a tough position after it became obvious that private valuations during the pandemic had climbed far above public market multiples.

Many of the late stage private fundraisings in 2021 look crazy given today’s public valuations.

Tosi looks at the rising revenue multiples granted to public technology companies during the pandemic. Technology stocks diverged from the rest of the S&P 500 and climbed beyond 12x forward revenue multiples.

Now those technology stocks have fallen back to 8x forward revenue, where they traded in early 2020.

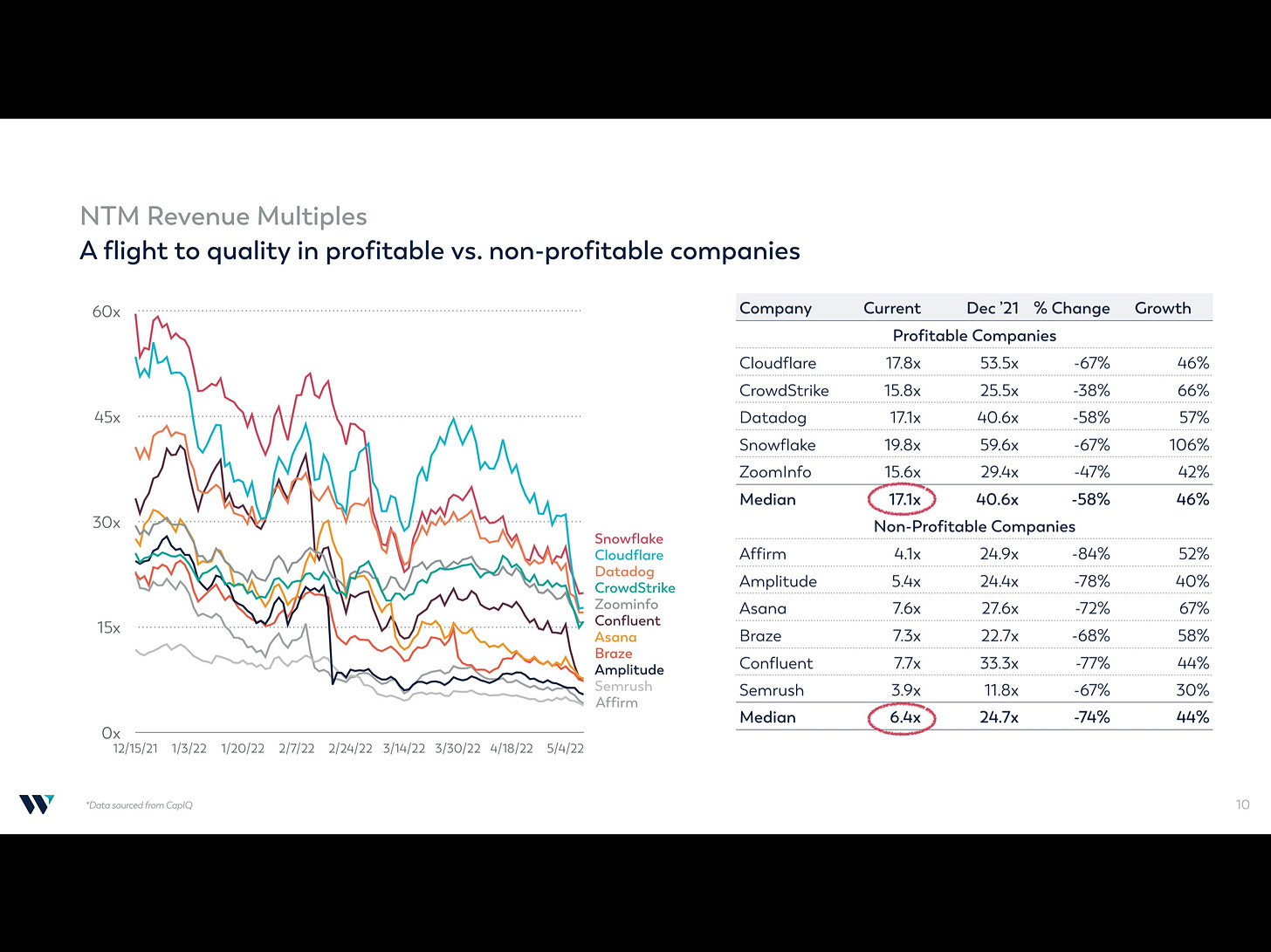

Public technology companies that don’t turn a profit have seen their stocks drop like a rock.

Tosi shows that a group of six unprofitable technology companies is trading at a median of 6.4x their next 12 months revenue, while a group of profitable public tech companies is trading at 17.1x the companies’ median next 12 months revenue.

That’s about as clear an illustration as you can get of the flight to profitability.

While both sets of companies have seen their revenue multiples fall, profitable companies are getting much more favorable multiples than unprofitable ones.

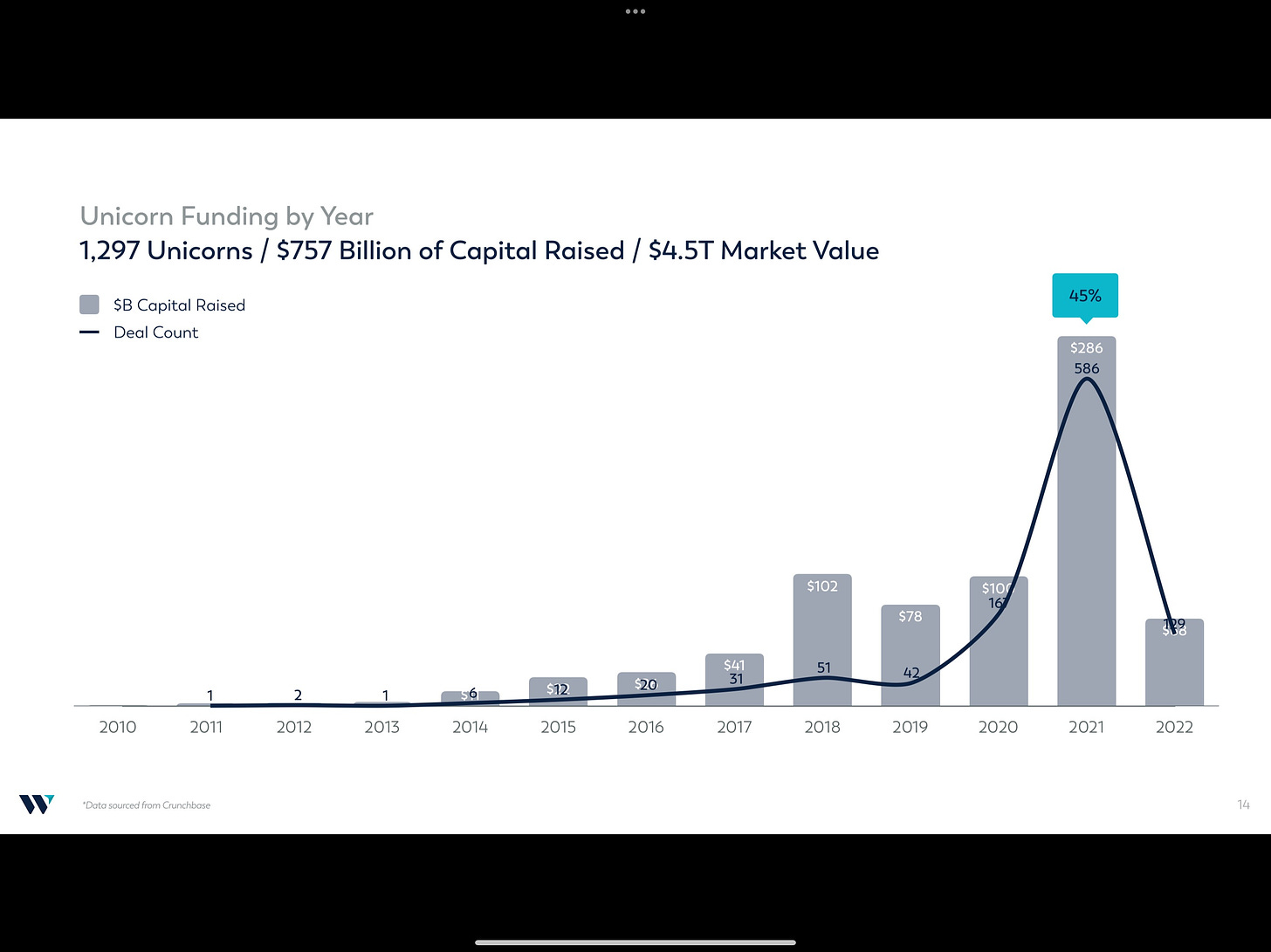

The number of unicorns exploded in 2021. But it was always going to be hard for the public markets to bear that many companies.

Tosi told me that 90% of companies worth more than $4 billion exit via the public markets. But it would take years for the 1,297 unicorns to go public.

Almost exactly 1,000 companies went public in 2021. Many of them were not technology companies. And this year, the pace of technology IPOs has slowed to a halt. It would take an extraordinary push to get all those unicorns public and many of them are never going to trade on the public markets.

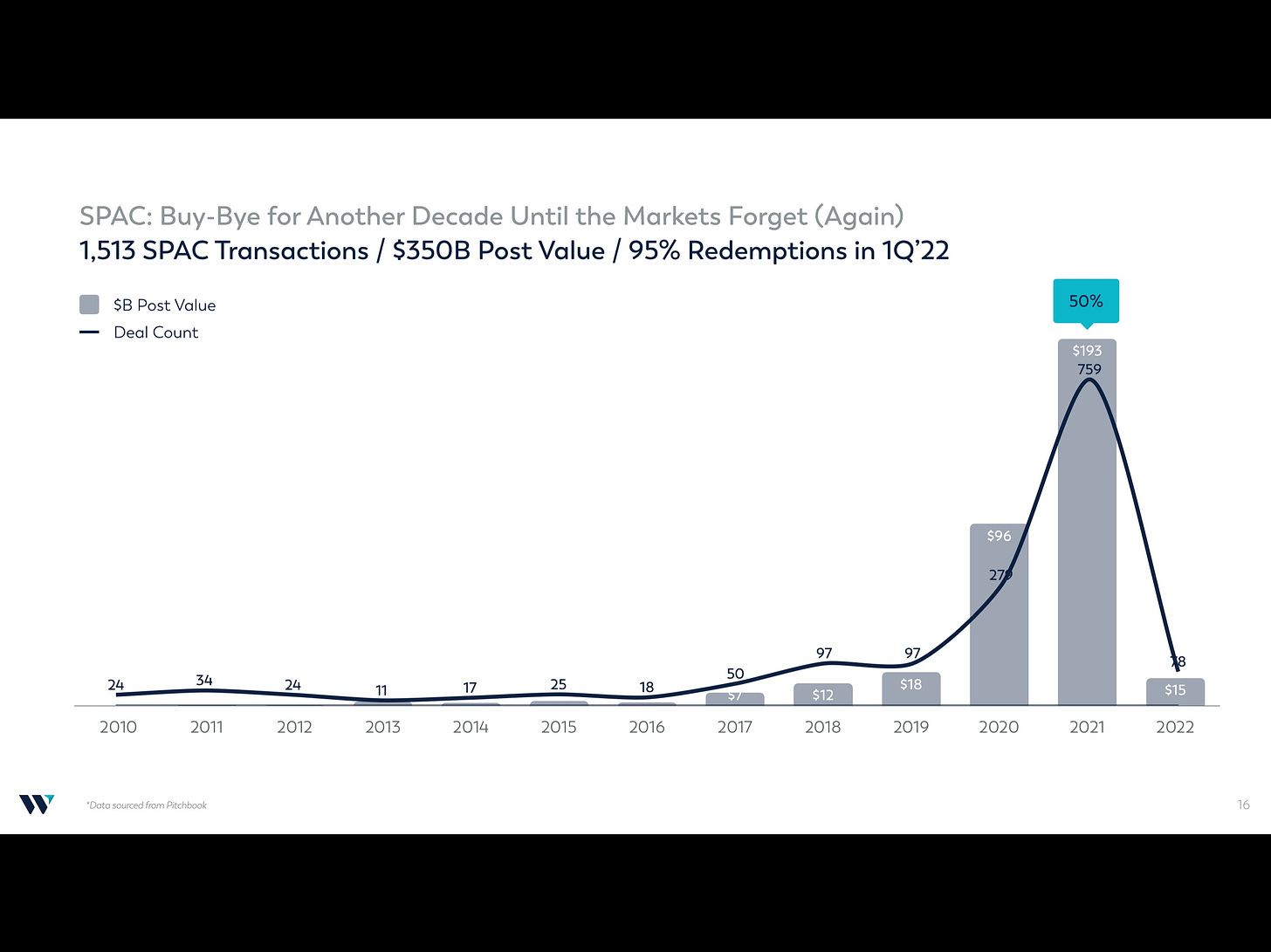

The number of companies that are getting taken public via special purpose acquisition companies is cratering. The SPAC — which allowed companies to provide prospective investors forecasts about future revenue — was a refuge for speculative technology companies that needed to find a way to the public markets. With banks like Goldman Sachs shying away from SPACs, that window seems to have closed.

Two Stocks: Amazon and Shopify

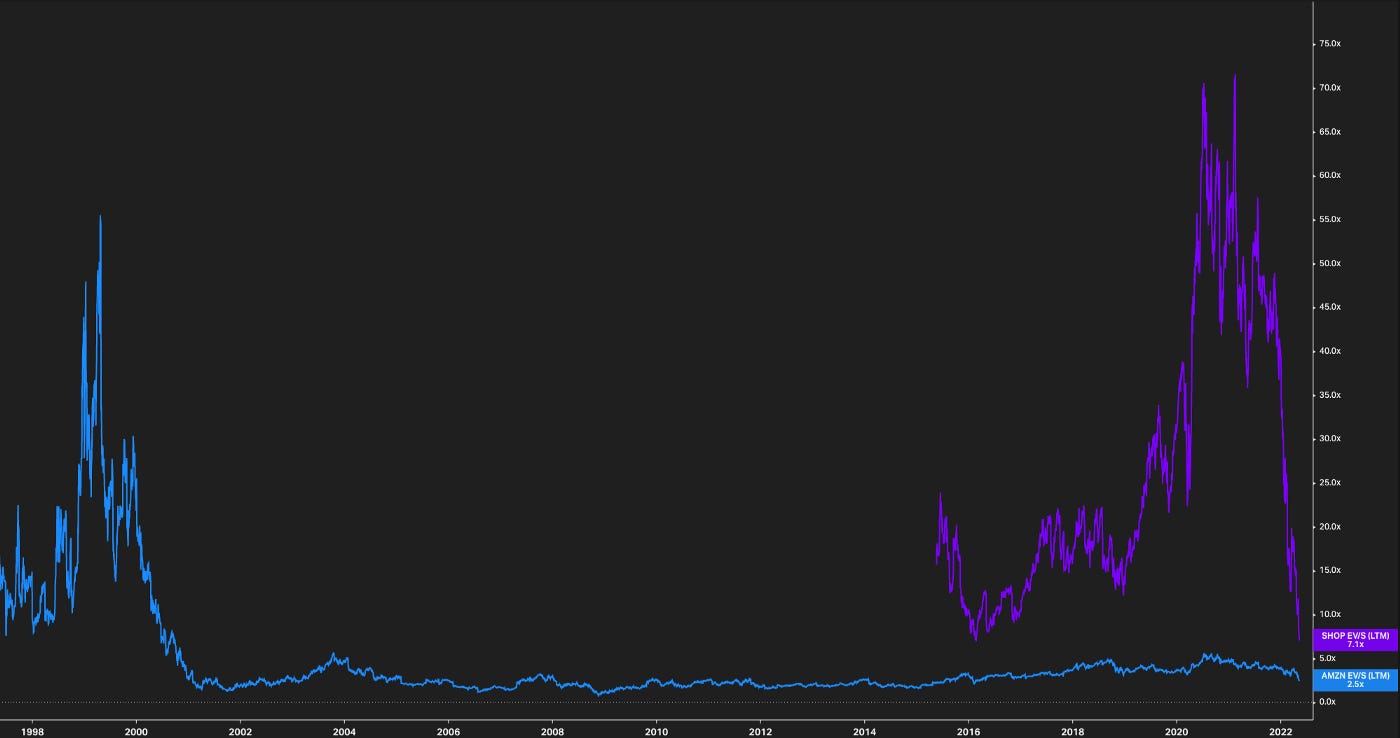

In Lightspeed’s look at the funding environment, the firm offered a telling chart:

No single metric shows the magnitude of the current downturn more than the dramatic retreat in revenue multiples for technology businesses. Witness, for example, the rise and fall of AMZN in the dot-comm bubble vs. SHOP in the last year. AMZN declined from ~55x trailing revenues to ~1x, while the latter is currently in free fall from ~71x trailing revenues to ~7x — an all-time low:

These eerily similar graphs remind us of past corrections — namely, the financial crisis of 2008–2009, the dot-com bubble burst of 2000–2002, and the Black Monday crash of 1987. Compared to these corrections, the current crisis shares some pathologies (e.g. speculative asset bubbles, Fed rate hikes), but others are novel (e.g. post-COVID headwinds, war in Ukraine, supply chain disruptions, ETF outflows). Each of these periods created prolonged and dramatic valuation downturns that culled the herd of startups, forcing significant changes across the tech industry.