The Anti-Portfolio

Bessemer Venture Partners is a thoughtful firm in a world of loose money.

In 2009, Ethan Kurzweil, then a senior associate at Bessemer Venture Partners, pulled out a $250,000 check from his jacket and slid it across the table to Twilio CEO Jeff Lawson at a diner in San Francisco. Lawson had been pressing Bessemer to lead a Series A round, but the firm decided it would be better to give Lawson a smaller investment to see if Twilio’s customers took to its new telephony products.

“Twilio is a promising young company with a bold vision to make voice applications as easy to set up and maintain as web applications,” Kurzweil and a group of other Bessemer staffers wrote to the partnership back in 2009. “We’d like the opportunity to review more data before making a determination on the full Series A and therefore strongly recommend making this angel investment.”

The seed extension check wasn’t exactly what Lawson was hoping for. After the meeting, Lawson called his lawyer to ask him what to even do with the check. “There's no contract. What's the deal?” Lawson remembers asking him. Ultimately, Lawson didn’t cash the check. But he did kick the Series A down the road, accepting $125,000 from Bessemer as part of a seed extension.

It was an era in venture capital where investors believed they had some amount of leverage over startup founders. Elite venture capital firms like Bessemer still thought they could make entrepreneurs wait for their money.

Every venture capital firm is defined by its big wins. I’ve spent the past few months talking to current and former investors at Bessemer to understand what makes the firm tick. I think the key to understanding Bessemer today is two iconic investments — Twilio and Shopify. Both companies have radically transformed the startup world as companies try to copy their business innovations. Bessemer held shares in both companies until about two years after they went public. But Twilio and Shopify have seen their values soar on the public markets this year. Bessemer’s investments in both companies offer telling case studies showing how it does deals and what it sees that everyone else doesn’t.

Going Big on Software As a Service

At first, Bessemer proved too cautious with Twilio. A few months after the seed extension, Albert Wenger, at Union Square Ventures, swooped in and led a $3.7 million Series A round in Twilio that valued the company at $12.4 million post-money, according to Pitchbook. That funding round allowed Union Square to cheaply build a 14% stake in Twilio at the time of its IPO in 2016.

Bessemer wouldn’t make the same mistake for the Series B. The firm whipped up a Twilio app to close the deal with Lawson. Twilio’s CEO called a number and a voice on the other end of the line said, “Press 1 for a $10 million investment, Press 2 for a $15 million investment,” and so on. Bessemer partner Byron Deeter pitched Lawson on taking the firm’s money. Ultimately, Bessemer led a $12 million investment in Twilio at $52 million post-money. Deeter took a board seat.

Deeter, who is 47 years old, is Bessemer’s best showman and cloud expert. He’s the public face of the firm. In another life, he could have been a big company CEO. One former Bessemer employee described him as “a guy who actually cares about people.” Deeter organized Bessemer’s first cloud conference in 2007 and created a popular index of cloud companies in 2011.

In 2012, Deeter approached Lawson about leading the company’s Series C. As Lawson remembers it, Deeter told him, “I’ve got a ton of conviction and these boneheads don't get it.” Bessemer led Twilio’s Series C round in 2012, valuing the company at a quaint $187 million. The next year, when Deeter tried to pull the same move, Lawson insisted that the company needed to raise money from an outside investor. When Redpoint Ventures won the deal, Lawson let Bessemer co-lead the funding round.

Ultimately, Bessemer owned 28.5% of Twilio when the company went public in 2016. The Twilio IPO gave the company a $1.2 billion market value and by the end of the first day of trading the company was worth $2.4 billion. It was a great moment for Bessemer.

Today, Twilio is worth $67 billion. Even Bessemer — a firm that went long on Twilio and software-as-a-service businesses generally — didn’t see that coming. Deeter still sits on Twilio’s board, but Bessemer distributed Twilio shares to their investors two years after the IPO. If those limited partners sold, they missed out on billions in potential returns.

“Personally, I wildly underestimated the size of some of these tech end markets in internet and in software,” said Jeremy Levine, a partner at Bessemer.

Bessemer Venture Partners traces back to 1911 when Henry Phipps Jr., the co-founder of Carnegie Steel, created his family office. The Phipps family spun out the venture firm in 1974, just two years after the founding of Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins. Then based in New York City, Bessemer opened a Silicon Valley office in 1979, but the office later went dormant. David Cowan moved to Silicon Valley in 1996 and re-opened the office in Menlo Park. The office moved to Redwood City in 2018.

Today, Bessemer Venture Partners — or BVP as it’s often shorthanded — is among the top dozen most prestigious Silicon Valley venture capital firms. These days, the Phipps family accounts for about one-third of the firm’s capital. The firm’s U.S. partners are split between offices in Redwood City, San Francisco, New York, and Cambridge, Massachusetts. Adam Fisher has scored a string of wins out of Israel, including Wix.com and Fiverr. Partner Alex Ferrara is opening up the firm’s office in London later this summer.

Bessemer has long had an associate program where it recruited investors as they graduated business school. Levine, who has been at Bessemer for 20 years, helped the firm build out an analyst program in 2005 that had young people, fresh out of college join the firm and start hunting for promising startups. Between the two programs, a number of top Silicon Valley venture capitalists learned the ropes at Bessemer by cold-calling CEOs and searching for the diamond in the rough. “The difference is they were not just hustlers, but they were smart hustlers,” says James Cham, an investor at Bloomberg Beta and a former senior associate at Bessemer. Accel’s Philippe Botteri, Andreessen Horowitz’s Chris Dixon and GGV’s Hans Tung all had stints at Bessemer.

Levine, who is 47 years old, said that when he joined the firm Bessemer had about 15 investors and now it’s more like 45. “Most investment firms are run by one or two people and eventually they retire or die — that’s a guarantee,” Levine says in his typically mordant fashion.

With the rise of Andreessen Horowitz, Bessemer’s investing approach started to look even more unusual. Where Silicon Valley VCs prized pattern matching CEO personalities and resumes, Bessemer built out detailed industry roadmaps and hunted for companies smartly positioned to grow into the industries that Bessemer’s partners envisioned. The more crowded the venture capital landscape became, however, the harder it’s been for Bessemer to find companies that Silicon Valley has overlooked.

When Andreessen Horowitz launched in 2009, the firm boasted that all of its partners were former operators. Meanwhile, Bessemer’s partners are almost universally professional investors. Andreessen Horowitz blew up valuations. Bessemer obsessed over keeping them sane.

Even as the world changed, Bessemer has done well. Bessemer’s investments in Pinterest and Twilio have put the firm’s seventh investment fund — a $1.1 billion pool of capital — on track to return the fund at least four-fold after accounting for the money invested. Sources told me that the firm’s next fund — a $1.6 billion fund — is on track to pay back at least four-times the money invested with investments in Twitch, Intercom, PagerDuty, Procore, Rocket Lab, and ServiceTitan. Bessemer declined to comment on its returns. This year, Bessemer announced $3.3 billion in new funds, split between a $2.475 billion venture fund and an $825 million growth fund.

Bessemer partner Steve Kraus’ portfolio company Bright Health just went public.

This year, Cowan’s portfolio company Auth0 sold to Okta for $6.5 billion; Bessemer owned 20.7%. He’s one of five investors at Bessemer to return $1 billion to the fund with a single investment. Cowan, 55, helped Bessemer develop the earliest underpinnings of its software as a service roadmap, understanding the value of recurring revenue businesses that needed early infusions of cash to generate consistent financial returns. He signed off on the early seed check in Twilio. And he pushed Bessemer to invest in companies looking to outer space even though many of his colleagues were skeptical.

On one level, Bessemer is doing fantastically well. It’s got great returns and the firm’s funds consistently rank among the top quartile or two of venture capital funds. The firm’s limited partners are making money and its partners are making out fantastically. (The firm’s members are allowed to invest alongside deals thanks to the unique terms the firm inked in its spinout from Bessemer Securities. The firm commands 30 percent carry and gets to keep much of its management fees.)

But venture capital firms always want to do better, and Bessemer is facing competition from all sides. Between Andreessen Horowitz, Tiger Global, and SoftBank, Bessemer has year-after-year scrunched up its nose at rising valuations only to see new crazy, manic actors enter the scene. Some of Bessemer’s best investments, including Shopify and Twilo, experienced a lot of their valuation growth on the public markets. Compare that to companies like Stripe, Uber, and Coinbase that reached multi-decacorn status as private companies, essentially forcing their venture capital backers to keep holding.

You can argue that Bessemer’s good governance, pro-IPO stance inadvertently hurt its returns. Acting like a responsible adult isn’t necessarily good business when everyone else is putting it all on red and their bets keep hitting.

One former Bessemer investor observed that if there was any real strike against the firm it was that the firm is “too smart for its own good.” Bessemer deconstructs markets, searches for needle in the haystack companies, and sometimes still gets outsold or outbid by a spendthrift rival. Levine — an investor in Yelp, LinkedIn, and Pinterest — worried about valuations so much in the second half of the 2010s that he slowed his pace of investing down. It was a period that saw the creation of new promising social apps like Discord and Cameo.

Another former Bessemer investor observed that if you’re a founder and want to know how venture firms might price your funding round, you should go to Andreessen Horowitz and Bessemer to get the high and the low end of the market. Even if that makes Bessemer the more discerning investor, it’s not a reputation the firm wants to cultivate with founders.

The firm is having a minor identity crisis these days. Levine — the firm’s soul, its cerebral and cynical marketplace investor — recruited Amazon executive Jeff Blackburn to join the firm. The hire was a coup. Deeter described Blackburn as a “top three executive at one of the world’s top three companies.” Blackburn was the exception that proved the rule — an experienced operator amidst a sea of seasoned investors. But the outlier didn’t last long. Five weeks after his first investor meeting at Bessemer, I reported that Blackburn was leaving the firm. A few weeks later it was announced that Blackburn was returning to Amazon to run its streaming service, which now included a new trophy — MGM, which Amazon was buying for $8.45 billion.

Another high-profile hire looks like she’s going to be sticking around. Shannon Brayton, who spent nine-and-a-half years at LinkedIn, left as the business networking company’s chief marketing officer. For a brief moment she was going to Stripe to run communications. Something happened. One source told me that Stripe soured on Brayton after The Information reported on the internal announcement. Instead, Stripe hired Google communications VP Peter Barron. And Brayton landed a job at Bessemer that she seems overqualified for — but one that won’t require running a 700-something organization at LinkedIn. She hopes to grow her team to ten people by the end of this year.

At Bessemer, Brayton faces the kind of tailwinds you want in marketing. The product is working; Bessemer has a good track record and returns. It just needs to compete in a world where capital is ubiquitous and venture capitalists grow ever more shameless in promoting themselves. Before joining Bessemer, Brayton was an active angel investor with more than 30 startup investments.

Bessemer’s knack for training top talent has been a double-edged sword. It’s been one of the most prolific incubators of female venture capitalists, but many of them have gone on to other jobs. Levine’s protégé Sarah Tavel is at Benchmark. Deeter’s protégé Kristina Shen left for Andreessen Horowitz. And Anna Khan is a general partner at CRV.

Talia Goldberg, who is a partner at 30 years old, joined Bessemer full-time after she graduated from college at the University of Pennsylvania. She’s still there. She’s a board observer at Shippo, ServiceTitan and Papaya Global. “I have been very much the product of Bessemer’s talent development and partner development model,” she told me.

This year, Bessemer promoted Mary D’Onofrio, Michael Droesch, and Tess Hatch to partner.

The core inner sanctum of the firm — the Deer Management Company — consists of Cowan, Levine, Deeter, Kurzweil, Kraus, Fisher, Ferrara, Bob Goodman, and Brian Feinstein. Bessemer’s Chief Financial Officer Sandy Grippo and General Counsel Scott Ring are also part of that leadership group.

The Anti-Portfolio

In August 2012, Brian Armstrong emailed Kurzweil, then a vice president at Bessemer. Armstrong wrote:

Was great chatting about bitcoin and coinbase yesterday. Not that I put much stock in such things but TheNextWeb seemed to think we were one of the top ten companies at demo day yesterday.

We have 200k committed so far of our 500k round (including two YC partners who invested personally). The cap is 10M and we're looking to close the round in the next two weeks so we can get back to work on the site.

What questions can I answer for you in the next two weeks that would cause you to invest in Coinbase?

Kurzweil responded brusquely:

Hey Brian — thanks for the follow up. There’s real [sic] no questions you could answer that would cause me to invest! It’s too early for us; we don’t do much seed investing unless we have a specific thesis in an area and we don’t here. Good luck.

It was a moment where Bessemer’s thesis-driven approach led the firm to miss the forest for the trees. Eventually, Kurzweil, who is now 42 years old, started to form a view on bitcoin — but Union Square Ventures, like they had with Twilio, moved faster. USV was willing to pay more than Bessemer probably would have anyway, Kurzweil says. Then, Andreessen Horowitz led the Series B at a $150 million post-money valuation.

“The moral for me is sometimes early in a roadmap — go with the flyer. I was trying to wait until I had the perfect thesis to go to him, half the thesis would have been fine,” Kurzweil reflected, “I also misperceived that I had more time to formulate a thesis.”

That Kurzweil (whose father is futurist Ray Kurzweil) shared his Coinbase misadventure with me is fairly unusual for Silicon Valley. It’s Bessemer trying to prove its radical transparency in a carefully curated world. In that same vein, Bessemer publishes its Anti-Portfolio — the companies it missed one way or another. The list includes Airbnb, Apple, Facebook, Tesla, Snap, PayPal, and Zoom.

During the dot-com boom, Cowan originally proposed creating a list of the firm’s big misses to differentiate Bessemer from its rivals. Some of the firm’s partners thought the anti-portfolio was a horrible suggestion. Felda Hardymon — who serves as the firm’s informal historian — was the only partner to really embrace the idea.

The firm’s entry on Facebook reads: “Jeremy Levine spent a weekend at a corporate retreat in the summer of 2004 dodging persistent Harvard undergrad Eduardo Saverin’s rabid pitch. Finally, cornered in a lunch line, Jeremy delivered some sage advice, “Kid haven’t you heard of Friendster? Move on. It’s over!”

The Moldovan Who Sourced Shopify

I had to guess former Bessemer analyst Daniela Bechet’s email address. She’d long ago left Bessemer to return to her home country of Moldova. I wrote to her that I’d heard that she’d originally sourced Bessemer’s investment in Shopify, the ecommerce company, today worth $193 billion.

She emailed me: “I can share the perspective on cold calling and spamming hundreds of entrepreneurs for two years until the lucky day that one Tobias Lutke answers kindly: let’s talk, we are finally considering an investment.”

She called me this past Monday from Moldova. I could hear her young children in the background. She was on maternity leave. In the years since her time as an analyst at Bessemer, she’d worked with the Prime Minister of Moldova to improve the country’s technology infrastructure and worked on the business side of a Moldovan investigative reporting outfit.

But way back in 2010, she left Bessemer defeated, having spent the time during the financial crisis trying to source startup investments. By the time she left, Bessemer hadn’t invested in any of the roughly 900 companies that she’d talked to over her two years as an analyst. Bechet reflects that she found it really hard to watch her investment ideas die. “Deals were dying every week,” she says. “This feels like a song,” she mused to me over our transatlantic WhatsApp call. She started singing a little tune.

Tavel, who was an analyst the class before Bechet, had sourced Cornerstone OnDemand and Yodle, among others. Later as Tavel climbed the ranks at Bessemer, she would identify Pinterest for Bessemer.

“I’m thinking I’m doing something wrong,” Bechet remembers thinking. “I was burnt out.”

As Bechet was wrapping up her time at Bessemer, Shopify CEO Tobias Lütke finally replied to one of Bechet’s persistent email messages. He wrote her: Shopify is ready to fundraise, and he would like to talk to her.

Bechet attended a call along with Ferrara and Trevor Oelschig, as she remembers it. Bechet who was the most junior of the people on the call remembers already having one foot out the door. As deal talks progressed, she left Bessemer in August 2010.

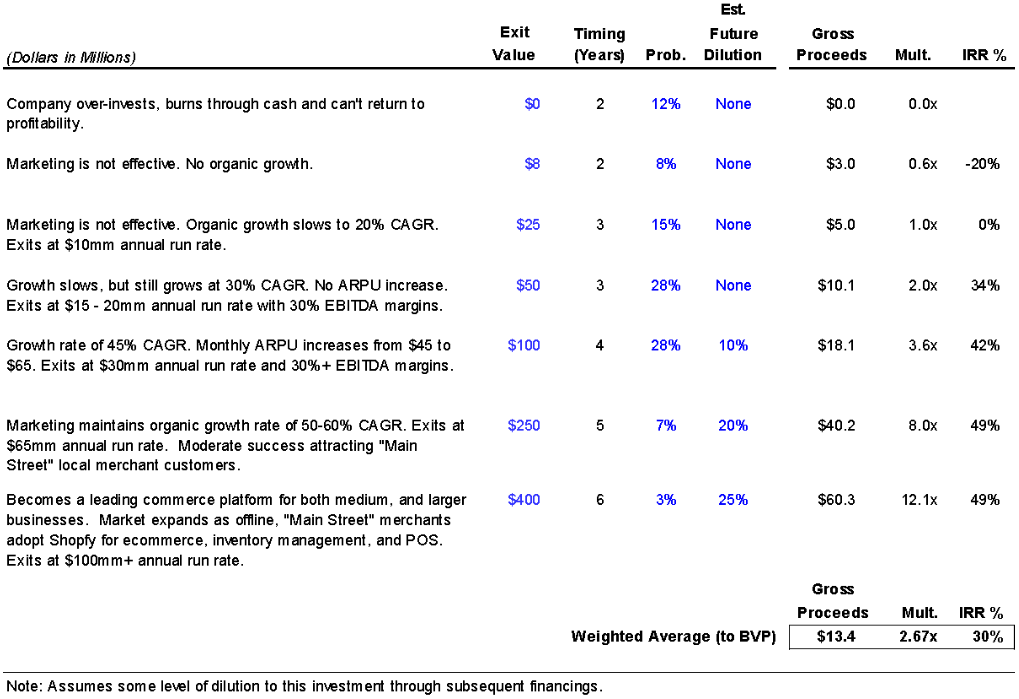

Ferrara and Oelschig wrote up a memo dated Oct. 12, 2010, that outlines Bessemer’s case for an investment in Shopify. At the time Shopify had just 24 employees and had raised $1 million. In the memo, the duo modeled out potential outcomes for Shopify. They imagine potential exits that value Shopify at $0, $8 million, $25 million, $50 million, $100 million, $250 million, and — in its homerun scenario — $400 million. The firm invested and both Ferrara and Oelschig took board seats.

Ferrara left Bessemer a few months later, looking for greener pastures, and Levine joined Shopify’s board, becoming one of the company’s key advisors.

Three years later Ferrara called some of Bessemer’s partners looking for advice on what his next move should be. Levine says, “We looked at the record of what he had done while he was here — his decisions were by and large really good, so we said come back.”

In 2015, Shopify went public. It was worth $1.27 billion at the time of its IPO. (Oelschig left to join General Catalyst.) Today, Shopify is worth $193 billion.

Bechet seemed to remember her time at Bessemer fondly. She recounted the core features of any good prospective Bessemer investment. But her memories are bittersweet. She didn’t make money off Bessemer’s stake in Shopify. If she’d stayed until the Shopify Series A closed, Bechet would have been allowed to invest a small amount of her own money alongside the deal.

“Shopify is not an anti-portfolio for Bessemer,” Bechet reflected. “Maybe for me, in my life, it's a bit of an anti-portfolio situation.”