The Limits of Founder Friendly: What Happened at Bench & Why Its Board Pushed Out Its Founder

I've got the story behind Ian Crosby's departure from Bench

Here’s the story of Bench Accounting, a Canadian startup made infamous by a departed founder’s viral account of his breakup with his board of directors. I’ve talked to former board members and former executives to piece together what happened. While the former CEO’s account is not without merit, I’ve learned that the CEO had lost the faith of some of the startup’s executives by the time the board intervened. Executives penned a letter asking for an investigation into the founder’s conduct as CEO.

Still, there’s a strong case to be made that Bench’s only path to success ran through its founding CEO. This is a complex story without straightforward heroes and villains.

This piece also has the unfortunate distinction of sparking the first express legal threat that I’ve received in the course of my reporting since I started this newsletter over four years ago.

‘I hope the story of Bench goes on to become a warning for VCs’

On Dec. 27, 2024, the founder of a suddenly defunct Canadian bookkeeping startup took to social media.

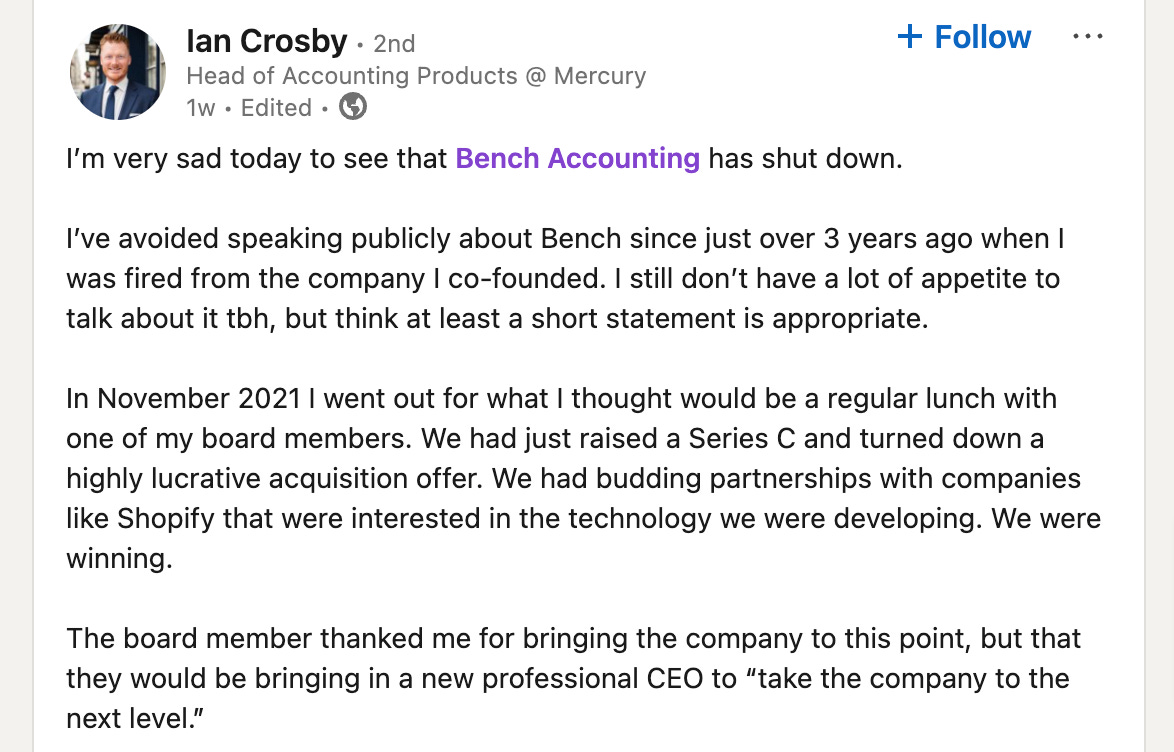

“I’m very sad today to see that Bench Accounting has shut down,” wrote Ian Crosby, the former CEO of Bench. Crosby offered a 375 word account of how the board pushed him out of the company he co-founded, concluding, “I hope the story of Bench goes on to become a warning for VCs that think they can ‘upgrade’ a company by replacing the founder. It never works.”

Crosby’s post on X has attracted 4.8 million views and his LinkedIn post has drawn hundreds of comments. His post became an end-of-year cause célèbre among the many people inclined to show their fidelity to founders.

Parker Conrad, a founder who knows something about being pushed out of the company he created, asked Crosby which VC partner had done the deed.

Shopify CEO Tobi Lutke, who hired Crosby after he left Bench, posted that replacing Crosby “is what killed the company. too many such stories in Canada.”

Andreessen Horowitz partner Scott Kupor asked “who were the VCs?”

Investor Jason Lemkin wrote, “So sorry man. I don’t know the details but I can’t think of any situation where it makes sense to replace a founder CEO outside of fraud, ethics issues, etc. Or unless the burn rate is out of control and there is no one to write the next check.”

I played my small part in the board witch hunt, posting a screenshot of PitchBook’s list of Bench directors. Amjad Masad, a founder-who-really-loves-founders, ran with the screenshot, posting the image along with a warning message, “VCs to avoid (with a ‘fuck off’) If some are innocent, they should come out and out the culprit. Pic by @EricNewcomer.”

Masad’s post was too half-baked and scorched earth for my taste. But X is always itching for a new fight.

Crosby’s viral social media posts had traveled farther than he could have ever expected, validating every founder who feels like their board members are ready to push them out of the startup at the first sign of trouble.

I started fielding entreaties from people unfairly implicated in the effort to track down the board members responsible for Crosby’s ouster. I tweeted, for instance, that one investor had been a board observer for his previous VC firm and had stepped away before Crosby even left Bench. (Masad tucked my finding into a reply to his own fiery tweet.)

So having now entered a conversation I knew very little about, I set out to figure out some facts. What was Bench Accounting? Why had Crosby been pressured to leave? Did the board members have a good reason? Who were they? What did the companies’ executives think about their boss’s departure?

As is the case for most things, the Bench story is more nuanced and complicated than can be summed up in a short social media post. You probably won’t be surprised to hear that Bench board members have been privately frustrated by Crosby’s account. But you may not be aware that some former Bench executives have been angry about Crosby’s social media posts. Others have come to his defense.

My reporting here has been conducted anonymously. I spoke with several former board members and a number of former executives. I’ve given the major players a chance to respond to the facts that I’m laying out here. One of them sicced their lawyer on me.

Here’s what happened at Bench

Bench Accounting — based in Vancouver and founded by Adam Saint, Jordan Menashy, and Crosby — hit its first big break when the startup was accepted to the Techstars NYC accelerator in 2012.

The startup built accounting software, powered by a team of full-time Bench bookkeepers, for the smallest of small businesses. The startup’s services-heavy approach limited its potential profit margins and attracted customers whose financials were in absolute disarray.

In 2019, corporate credit card startup Brex approached Bench about potentially acquiring it, sources tell me. In March 2020, top Brex executives were in Vancouver at Bench’s offices to hammer out a deal. Inside Bench, people believed that Brex was eyeing an acquisition price between $200 million and $300 million. But a suddenly emerging pandemic helped scuttle the deal talks at the time.

About a year later in 2021, Brex came back to the table and Crosby leveraged that conversation to initiate an inside Series C funding round instead.

In 2021, three years following the company’s last real fundraise, Bench raised a $30 million Series C round led by the venture capital firm Contour Venture Partners. Shopify participated in the funding round. Bench also extended its credit line by $30 million. The company said in its announcement, “Launching today, Bench now offers a first-of-its-kind integrated offering that includes banking, cards, payroll, full-service bookkeeping, taxes, and advice in a single streamlined software and service offering for small businesses.”

The company attracted roughly 10,000 customers and generated about $35 million in annualized revenue in 2021 while Crosby was CEO.

Contour became one of the four largest investors in Bench, alongside Altos Ventures (Series A lead), Bain Capital Ventures (Series B1 lead), and Inovia Capital (Series B2 lead). Anthony Lee represented Altos on the board, Indranil “Indy” Guha represented Bain, Shawn Abbott represented Inovia, and Matt Gorin represented Contour. Altos and Bain Capital Ventures are Silicon Valley venture capital firms, Inovia is based in Canada, and Contour is based in New York City.

In less than a year, the company’s investor board members began to get cold feet about Bench’s trajectory under Crosby. Abbott had enthusiastically pushed the company to go big — while maintaining the role as the board’s friendly skeptic, interrogating Crosby’s plans. Gorin was the worrier — his firm had risked a lot of money on Bench and he largely seemed to want the company to play it safe and keep costs down. Guha, who left Bain Capital Ventures in 2018, stayed on Bench’s board but wasn’t the most active board member. Lee, who had joined the board the earliest, projected a friendly attitude and air of support for Crosby.

Board members started to harbor complaints about the way Crosby was running the business as Bench fell behind on its financial plans.

The business kept consuming more cash — about $1.5 million a month — and was burning through its equity capital much faster than expected.

Bench needed to find a way to scale its service-intensive business without having to hire endless numbers of human bookkeepers. One proposal was to provide bookkeepers support staff so that they could serve more clients at once.

Some board members and executives were skeptical of Crosby’s effort to build a banking business. The startup was dedicating about two-thirds of its engineering resources to exploratory lines of business, separate from Bench’s core bookkeeping service. (If Bench had been executing more profitably on its core business, investors might have been more inclined to go along with the new bets.)

Board members heard from some executives who were frustrated with Crosby. The company regularly turned over executives. Some executives thought Crosby was overly harsh with his feedback — and was too willing to deliver it in front of other employees. Members of the board learned that executives had been disturbed by an executive coaching team that Crosby brought on. The coaches often sat in on meetings with executives and encouraged them to dig into their issues with each other.

Finally, while Bench had raised its Series C as public and private tech stocks were trading at sky-high multiples, toward the end of 2021 there were signs that tech startups would not benefit from such optimistic multiples for much longer.

So the four investor board members met privately and agreed that they needed to do something drastic. One of them would meet with Crosby and suggest dire action was required. They agreed on a script for Inovia’s Abbott to deliver to Crosby.

One board member relayed the plan to Menashy, a Bench co-founder who remained on the board. The board member told Menashy that the plan was to ask Crosby to step aside, according to a person familiar with the matter.

On December 1, 2021, Abbott met Crosby for lunch at Fable Kitchen in Vancouver.

In Crosby’s social media post, Crosby describes the meeting this way: “The board member thanked me for bringing the company to this point, but that they would be bringing in a new professional CEO to ‘take the company to the next level.’”

This is where accounts differ slightly.

As people close to the board remember it, Abbott initially presented Crosby with a couple options: Crosby could try to sell the company or bring on another executive, potentially a new CEO, to work with him. The plan was to encourage Crosby to lead the effort to find an experienced executive to support him in scaling the company, these people say.

The board believed that Bench’s cash burn was out of hand, the bookkeeping product was struggling to scale, and that the complaints from Bench executives about Crosby’s leadership were becoming untenable.

After the meeting, Crosby emailed the board that while he objected to their decision to replace him, he wouldn’t stand in the way of finding a new leader.

On Dec. 5, 2021, a few days after Abbott sat down with Crosby, Bench executives sent the investor board members a letter with a number of complaints about Crosby, including “bullying.” The letter — which I’ve obtained a copy of but am not publishing1 — makes accusations that I have not been able to substantiate. Crosby’s attorney called the letter “untrue and defamatory” and threatened to take legal action against me if I published it.

The letter was ultimately signed by many of the company’s most senior executives besides Crosby, according to sources familiar with the matter. The letter asked the board to investigate their accusations.

The board asked Crosby to take a leave of absence to start an investigation after receiving the letter.

Crosby was informed that there had been a complaint against him but wasn’t informed about the letter from his executives, according to a person close to Crosby.

Crosby’s lawyers reached out to negotiate an exit from the company.

Crosby left his job as CEO, which he’d held for ten years, and he stepped off the board. After Crosby left, the board did not conduct the investigation.

To zoom out for a moment: This came during what you might call “peak wokeness.” The executive complaints about Crosby came during an intense moment for company culture when many tech companies were undergoing struggle sessions, closely parsing the behavior of their founders. At the same time, Crosby’s direct management style frustrated some of his executives, and some female executives felt singled out for negative feedback, sources tell me.

I think Crosby’s social media version of events looks too rosy given the reality that he had not only lost the confidence of his board but of some of his executive team as well.

If a CEO is running a costly strategy without a clear plan to raise more money, has lost the faith of his board, and has alienated members of his executive team, how far is founder friendly supposed to go exactly?

At the same time, just because a founder is delivering unsatisfactory results that doesn’t mean an off-the-shelf replacement will do any better.

One person involved in the saga said this was just a case of “everybody trying to do their best in a tough situation.”

Post-Crosby

The best case for keeping Crosby as CEO is that we know the counterfactual: things ended terribly.