Everything everywhere all at once.

Crypto currencies are tumbling and stable coins are looking far less stable. Bloomberg declared that more than $200 billion in crypto wealth had been destroyed in the crash. Coinbase’s stock price has fallen 77% so far this year.

Many companies that went public via SPACs are in trouble. Some biotech companies are trading at market capitalizations worth less than their cash holdings. Goldman Sachs is halting its work with SPACs as the Securities and Exchange Commission is (predictably) cracking down.

Tech stocks are falling across the board. The NASDAQ Composite is down 7% over five days and off 28% year-to-date. Even stalwart Apple has seen its market cap cut by more than one-fifth so far this year. Snowflake, a growth investor favorite, is down 58%.

With many of the most speculative pieces of the technology sector in retreat, it’s only fitting that the investors who bet the farm on high-growth tech stocks are suffering disproportionately.

In the bull market, SoftBank and Tiger Global became infamous for driving up valuations. Now they’re reaping what they sowed.

I got my hands on a Tiger Global pitch deck from Q1 of 2022. (Paid subscribers can see many of the Tiger slides for themselves below.) The slides help to paint a picture of the firm’s most important investments and offer some clues as to the predicament that Tiger faces right now.

I’ve also been talking to investors. Questions are swirling. Will any of the biggest investors shut down as stocks continue to tumble?

Today, SoftBank released its earnings report, offering information about its poor performance.

You might want to open this article on your browser since your email client is probably going to cut it off before the end.

SoftBank

In 2017 and 2018, SoftBank made a string of humongous bets on companies like WeWork, DoorDash, Didi, Coupang, and others.

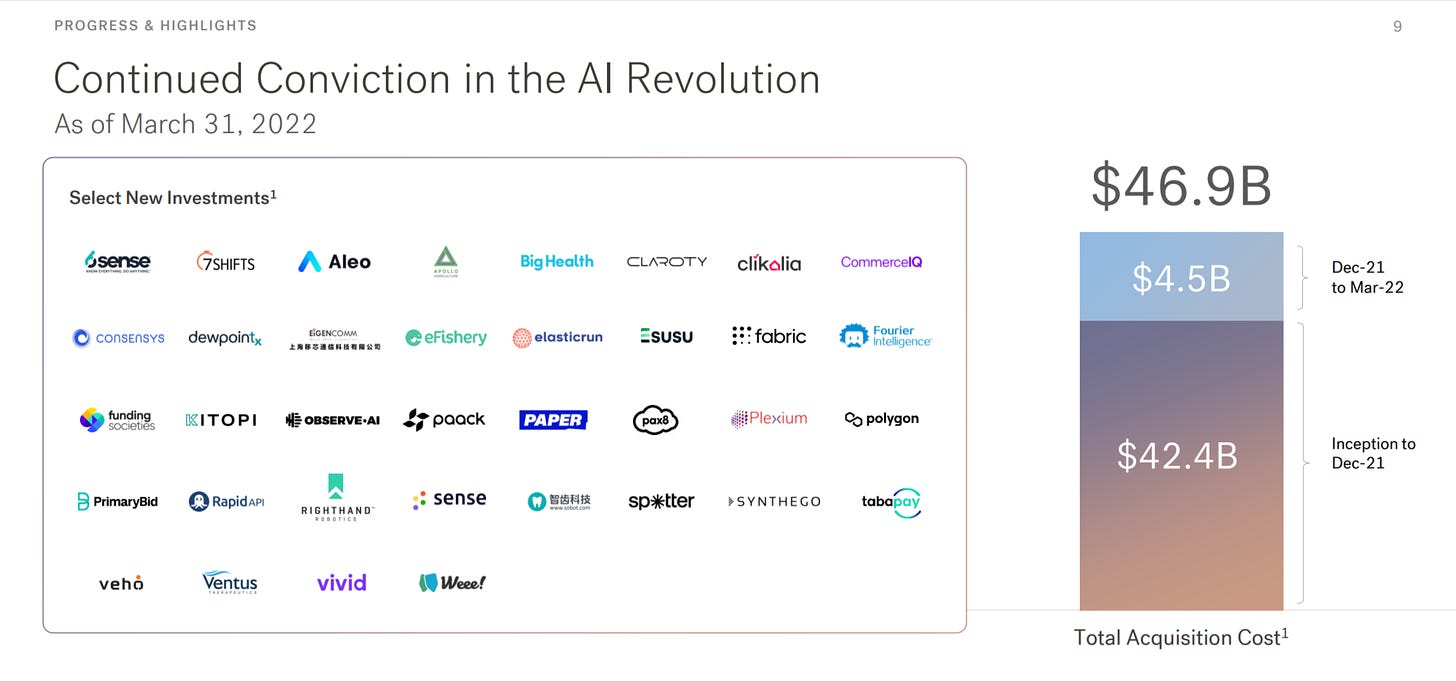

Then, the firm tried reviving that strategy with artificial intelligence companies in Spring 2021 as the stock market rebounded during the pandemic.

Today, SoftBank told investors that its two “Vision Fund” investment vehicles had racked up the biggest net loss ever: more than $26 billion for the fiscal year ending March 31.

SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son blamed the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But let’s be real: the firm went full tilt into the technology sector, which was inevitably going to correct. This is a cycle that Son knows all too well. He lost a fortune in the dot-com bust. He didn’t just watch the movie last time. He starred in it.

Like every great actor, Son thought that there was even more money to be made on the sequel.

Many of the companies that SoftBank invested in for its second, smaller Vision Fund are relatively obscure. Top Silicon Valley investors are going up against the firm less and less. Some of SoftBank’s most prominent investors have left.

SoftBank has emphasized that its fortunes aren’t tied to any single big name portfolio companies like Alibaba, Didi, or DoorDash — whose stocks have all been falling. But I don’t know why investors should have more confidence in the long tail of SoftBank’s portfolio.

The Information reported today that employees at IRL, one of SoftBank’s consumer portfolio companies, had questions about the credibility of their employer’s metrics.

That’s the kind of story I’d expect to see more often as the world attempts to explain why companies that were once valued in the billions suddenly see their values plummet.

SoftBank is planning to dramatically slow its investing pace this year. I hear the firm’s ability to make future investments is largely contingent on whether it can sell off some of its current holdings.

Tiger Global

Tiger Global’s founder has witnessed disaster first-hand.

The firm was founded by Chase Coleman III, who was an investment analyst at Tiger Management.

Tiger Management — which has spawned countless successors called Tiger Cubs — blew up in March 2000 just as the dot-com boom was unraveling.

Contrary to what you might expect, Julian Robertson Jr.’s Tiger Management had been betting on value stocks like US Airways — not speculative tech stocks. But ultimately the hedge fund unraveled and returned investors their money just as the dot-com bubble was bursting.

Now, this iteration of Tiger — Tiger Global — has become the posterchild for frenzied technology investing in the runup to this year’s crash.

We’ve entered a period that we might call the “Great Rationalization,” “The Powell Pounding,” or, perhaps, the “Ape-pocalyse.” Rising interest rates are pushing investors to flee companies (and crypto currencies) that don’t generate profits.

This week, the Financial Times reported that Tiger had lost $17 billion during the tech downturn this year.1

The run of poor performance means the firm — one of the world’s biggest hedge funds and a big investor in high-growth, speculative companies whose shares have tumbled since their pandemic peaks — has in four months erased about two-thirds of its gains since its launch in 2001, according to calculations by LCH Investments.

Meanwhile, Connie Loizos, writing for TechCrunch, reported that Tiger had almost depleted its $12.7 billion fund XV that it announced in March of this year.

Yet even that new fund — which reportedly took less than six months to raise and includes $1.5 billion in commitments from Tiger Global’s own employees — is almost fully invested already, according to a source close to the firm.

Last year, Tiger received $4 billion in net-asset-value financing from J.P. Morgan and other banks to invest with, according to Bloomberg. That allowed Tiger to deploy capital before actually closing the XV fund in March. That helps to explain how Tiger could already have deployed much of the $12.7 billion fund.

Raising debt to invest before raising money has become a popular strategy in the private equity industry. The strategy allows investors to deploy money faster and potentially juice their internal rate of return metrics.

You might remember a piece written by Founders Fund’s Everett Randle last year called “Playing Different Games” that argued that Tiger was trying to deploy as much capital as quickly as it could to reap management fees.

It looks like Tiger ran that playbook until the music stopped.

I don’t know exactly how much Tiger has left. Running low on capital would certainly further explain Tiger’s lurch toward Series A and Series B rounds.

The possibility that Tiger doesn’t have money to invest is fueling all sorts of speculation. Rumors are swirling. Reporters are frantically checking in with sources.

Call it Schrödinger’s Tiger: nobody knows if the cat is alive or dead.

Rival crossover investor Brad Gerstner, who runs Altimeter, took to Twitter to offer a mea culpa of his own.

So far Tiger, as is its tendency, has been publicly silent. (A spokesperson for the firm declined to comment for this article.)

In what’s perhaps a sign that Tiger has humbled its ambitions, this year Tiger paid Goldman Sachs to raise checks as small as $1 million for a $1 billion crossover fund that it’s calling Tiger Global Crossover, or TGX. It seemed rather small potatoes for a firm that told prospective investors that it had $98 billion in assets under management collectively.

I got my hands on the fundraising deck for that fund.

What’s really interesting isn’t what Tiger says about TGX but what Tiger says about its overall strategy across its much larger public and private funds. Those funds appear deeply interconnected, with one fund investing in a company one year and another fund investing the next.

For its TGX fundraise, Tiger tells investors how it’s been doing as of late last year. That was a far better time for the stock market.

So read everything you see below with that at the front of your mind.